Yoga for Strength & Flexibility: The Ultimate Guide

There are two qualities noticeable when you observe the practice of an experienced yoga practitioner: A seemingly perfect harmony of strength and flexibility.

Most people think flexibility is a requirement to practice yoga, but this is a misconception. In this blog, you'll learn why yoga is actually one of the most effective disciplines to develop both strength and flexibility.

What is flexibility?

An unrestricted and pain-free range of motion in joints is called flexibility. The joint is surrounded by soft tissues of muscles, ligaments, tendons, joint capsules, and skin. These soft tissues support the joints to function smoothly. Every person's musculoskeletal structure is different and therefore, flexibility differs in each individual. The range of motion is influenced by the mobility and elasticity of the soft tissues that surround the joint. A lack of stretching, especially when combined with activity can lead to a shortening of the soft tissue due to fatigue.

Flexibility and muscles

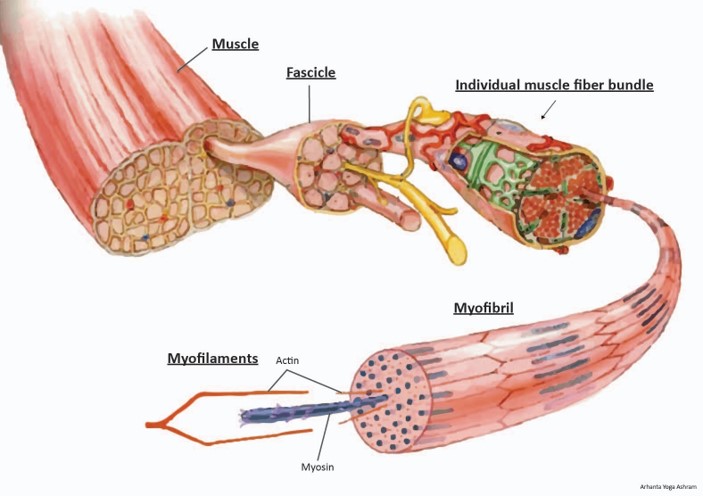

The specific function of muscles is movement. That movement is produced by muscle fibers. A muscle fiber consists of two types of proteins (actin and myosin), arranged in a long row. As soon as the nervous system sends the command to release calcium, these proteins get attracted to each other and contract toward each other. These two proteins pulling toward each other form the basis for any muscular contraction.

But what holds these proteins in place and guides them to contract in a particular direction? Connective tissue, or in this case, to be more specific, fascia. Now, this is only one single muscle fiber.

A group of muscle fibers joined together makes a muscle cell. These muscle cells are like the pieces of pulp in citrus fruit, each of which has its own layer of skin. In these muscle cells, the skin is a layer of fascia. A group of these muscle cells bundled together and wrapped with another layer of fascia and we have a muscle fascicle. A muscle fascicle can be compared to the wedge in citrus fruits, which is a group of pieces of pulp. And finally, the muscles itself is a bundle of fascicles that are surrounded with yet another later of fascia, called the epimysium. This outer layer can be likened to the peel of the citrus fruit.

So, muscles are layers and layers of fascia around contracting proteins. Therefore, when a muscle contracts, it is not only a row of proteins getting closer together and shortening the muscle. Every contraction of these proteins (actin and myosin) involves the fascia that is wrapped around them. Similarly, every time we stretch a muscle, the fascia can resist.

There are two types of muscle groups that create skeletal movement – agonists and antagonists. The agonists are the contracting muscles. While the antagonists are the muscles that must release and expand to allow movement. Myofascia (muscles) can only contract, they can’t stretch by themselves. Therefore, any skeleton movement is facilitated by the smooth coordination of the agonist muscle contracting and the antagonist muscle being stretched.

What restricts flexibility?

According to recent studies, it is possible to extend individual muscle fibers to approx. 150 percent of their normal length without tearing. But most physiologists suggest that improving the elasticity of muscle fibers is not enough to increase flexibility.

If muscle fibers don’t restrict flexibility, what does?

There are two different scientific schools of thought regarding the causes of restrictions on flexibility and methods of improvement:

The focus of the first research is on increasing the flexibility of the connective tissue.

The second research focuses on the nervous system and its feedback loop that influences muscle tone.

Yoga acts as a stimulant to both the methods of muscle reaction and is, therefore, an efficient way to improve flexibility.

Connective tissue lengthening through yoga

Connective tissue is a key component when we want to understand the balance of strength and flexibility in the body and how yoga can affect this balance. Connective tissue includes our bones, cartilage, muscles, fascia, tendons, ligaments, and scar tissue.

Connective tissues are tissues comprised of collagen and elastin. Collagen is responsible for providing strength and stability. And elastin, as the name suggests, is providing elasticity. Put together in varying proportions, these two proteins create an astounding variety of connective tissues.

We are concerned with only three types of connective tissue in regards to the study of flexibility: tendons, ligaments, and muscle fascia:

- Tendons are the strong tissues connecting the bones to the muscles. The stiff tendons are managed by fine motor coordination. The tendons have a stretch of just four percent and can result in tears or ruptures if forced to lengthen.

- Ligaments are more stretchable compared to tendons. Their function is to bind bones inside joint capsules. It is recommended to avoid overstretching the ligaments as it can destabilize the joints and cause injury.

- According to the studies, muscle fascia accounts for approximately 30 percent of the total mass of a muscle. It is the main contributor (41%) to the muscles’ movement resistance. Fascia separates individual muscle fibers and provides structure while transmitting force. Of all the structural components of our body which limit our flexibility, it is the only one that we can stretch safely.

Fascia and flexibility

We understand now that flexibility depends greatly on the health of our fascia. We experience limited flexibility due to our fascia getting ‘stuck’. Common causes are:

- Too much movement:

The connective tissues respond to the stress such as lifting weights by attempting to adjust locally. To increase the strength, it lays down new fibers of connective tissue (collagen). This makes the fascia denser and stronger.

- Not enough movement:

Inactivity can cause muscle atrophy. The fascia becomes rigid due to lack of stretching or any movement, which results in muscle weakness affecting the overall health.

- Injury:

An injury to any tissue changes stimulates repair mechanisms in the body. The body responds to injury by laying down extra collagen fibres, forming scar tissue over the injured area. These added layers of fascia can inhibit the fascia to slide along the adjacent layer of the fascia of the neighboring muscle. This can negatively influence the flexibility and the normal functioning of the muscles.

Example: Hamstrings

The group of three muscles, located at the back of our upper legs is called the hamstrings. This muscle group is ideal to demonstrate the principles of how fascia affects flexibility. Hamstrings contract hundreds of times every day. They contract every time we walk, every time we sit and every time we do conventional sports such as cycling or ball sports. If such daily activities go paired with only a little or no stretching, these three individual muscles start to become ‘stuck together; layers of fascia that separate them, start to connect with each other, and can’t function independently anymore.

Neuromuscular principles for improved flexibility

There are several ways that yoga influences our muscles through the nervous system.

1. Lower muscle tone

Hatha Yoga, with its steady and comfortable holds and focus on even, calm breathing stimulates the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The PNS governs the autonomic functions of our body when the body and mind are at a resting state. One of the many effects that the activation of the PNS has on our body, is a generally lower muscle tone – a lower ‘tonic contraction’. And as a result of this, when the overall muscle tone in the body is lower, the resistance to stretching is lower too.

2. Stretch reflex

Throughout our body, we have sensory receptors, that give the nervous system information about pressure, movement, and location. Muscles we have specialized receptors called muscle spindles. A muscle spindle measures the length of a resting muscle. If the length of the muscle increases suddenly, the muscle spindles will trigger a sudden and unconscious contraction to protect the muscle. Detailed research on the subject of improving flexibility has led physiologists to identify the stretch reflex as an important obstacle to increase flexibility.

Essentially, any kind of stretching, also slow and static stretching triggers the stretch reflex. When we fold forward into Paschimottanasana, the muscle spindles in our hamstrings begin to signal for resistance, increasing tension in the very muscles you're trying to stretch. That's why improving flexibility takes a long time. The prolonged and conscious stretching during yoga practice allows gradual progress in overriding and postponing the stretch reflex.

Get a free copy of our illustrated e-book 4 Surya Namaskara Variations for Vinyasa Yoga

3. Golgi tendon organs and PNF

In contrast to the muscle spindles that are located in the muscle belly, the Golgi tendon organs are located where the muscle and tendon meet. And whereas the muscle spindles measure an increase of muscle length, the Golgi tendon organs measure the amount of force in the tendinous area. If there is too much tension in the muscle due to contraction, the Golgi tendon reflex will trigger the muscle to relax in order to avoid injury.

When muscles contract (possibly due to the stretch reflex), they produce tension at the point where the muscle is connected to the tendon, where the Golgi tendon organ is located. The Golgi tendon organ records the change in tension, and the rate of change of the tension, and sends signals to the nervous system. When this tension exceeds a certain threshold, it triggers the lengthening reaction which stops the muscles from contracting and causes them to relax. Other names for this reflex are the inverse myotatic reflex, autogenic inhibition, and the clasped-knife reflex. This basic function of the Golgi tendon organ helps to protect the muscles, tendons, and ligaments from injury. The lengthening reaction is possible only because the signaling of the Golgi tendon organ to the spinal cord is powerful enough to overcome the signaling of the muscle spindles telling the muscle to contract.

The Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation or PNF has proven highly effective in quick and substantial improvement of flexibility.

To apply PNF principles to Paschimottanasana, try this: While bending forward, just short of your maximum stretch, engage your hamstrings in an isometric contraction—pushing your heels down against the floor. This isometric contraction of the hamstrings should last 5 to 10 seconds. Once you release the contraction, you’ll be able to move a little deeper into the forward bend.

The PNF technique manipulates the stretch reflex by having you contract a muscle while it’s at near-maximum length. While engaging the hamstrings, the Golgi tendon reflex is triggered, which overrides the signal of the muscle spindles and triggers the muscle to lengthen.

What is physical strength?

Now, we started this topic off with the seemingly perfect balance of strength and flexibility that we can observe in experienced yoga practitioners. In order to understand how we can build up this strength, we must first understand what it is.

There are different types of strengths. An Olympic weightlifter uses different skills than a gymnast. And there are other elements of physical strength such as stamina and endurance. Weightlifting requires a single attempt to display strength, whereas gymnasts perform a series of athletic movements for a longer duration.

When a muscle fiber contracts, it contracts completely. There is no such thing as a partially contracted muscle fiber. Muscle fibers are unable to vary the intensity of their contraction relative to the load against which they are acting. If this is so, then how does the force of a muscle contraction vary in strength from strong to weak? What happens is that more muscle fibers are recruited, as they are needed, to perform the job at hand. The more muscle fibers that are recruited by the central nervous system, the stronger the force generated by the muscular contraction.

In some exercises, we required a larger number of muscle fibers that can contract with huge forces over a short period of time. Other exercises required fewer muscle fibers at the same time, the muscle fibers alternate each other more as they contract and therefore last longer.

Strength, therefore, is a combination of the number of muscle fibers that are used to execute a movement and the density of the fascia surrounding them (especially the strength of the tendons and ligaments).

Muscle contractions

Muscles vary in shape and in size and serve many different purposes. Most large muscles, like the hamstrings and quadriceps, control motion. Other muscles, like the heart, and the muscles of the inner ear, perform other functions. At the microscopic level, however, all muscles share the same basic structure.

A muscle contracts, at a cellular level, the same way all the time. In fact, all muscle cells can really do is receive a signal that stimulates the nervous system to contract. Releasing the stimulus stops the muscular cells to contract.

The most basic contraction is called a ‘tonic contraction’. The constant low level of muscular contraction helps maintain an alert posture. When unconscious, this alertness created by the tonic contractions of the muscles is lost and we fall to the floor. When we are sedated, we also lose this basic muscle tone. And that is the reason why sedated patients are lifted by several nurses to avoid dislocation of any joint or any other injury.

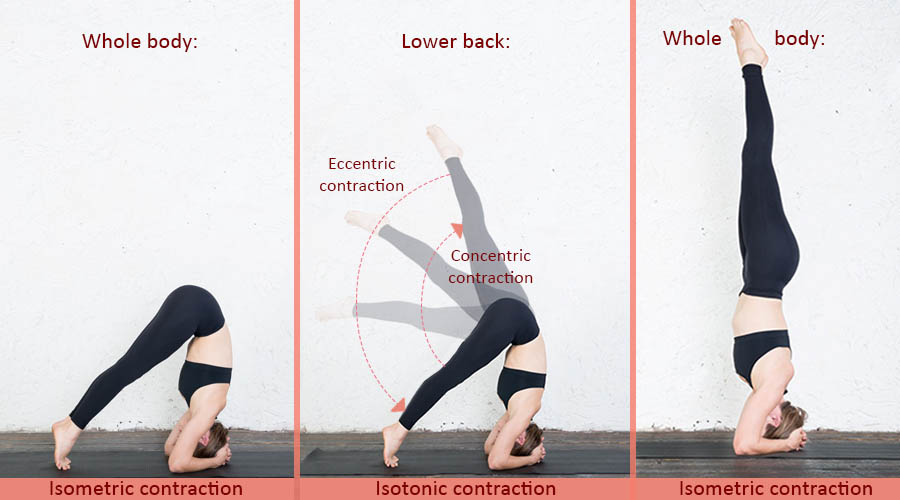

Active contractions can be divided into two categories:

Isometric contraction

- Pushing or pulling an immovable object, no movement takes place

- The load on the muscle > the tension generated by the contracting muscle

Isotonic contraction

- Successfully pushing or moving an object

- The tension generated by the contracting muscle is more than the load on the muscle

Isotonic contraction can be further divided into

Concentric contraction

- Agonist muscle decreases in length (shortens) against an opposing load

- E.g. lifting a weight

Eccentric contraction

- Agonist muscle increases in length (lengthens) as it resists a load

- E.g. lowering a weight down in a slow, controlled motion

Strength and flexibility in balance

When we think of the effect exercises have on our fascia, we can easily compare weightlifting in which we move our muscles mainly through an isotonic contraction with holding yoga postures for prolonged durations in which we engage our muscles in an isometric contraction.

It becomes obvious that in yoga we engage the muscles in a more elongated state, rather than only shortening them. By doing so, we essentially move and manipulate the fascia of the muscle so that its fibers are aligned with the length of the muscle and so that the various layers of fascia can slide along each other.

In contrast, when doing weightlifting, and other conventional exercises, we mainly focus on isometric contractions and as a result, we stimulate the connective tissue to lay down more fibers in order to be stronger.

Sthira Sukham Asanam

Isometric contractions are the foundation of a yoga asana practice according to the ancient principle of sthira sukham asanam. This ancient principle states that when your body and mind are steady and comfortable even when your body is challenged out of its comfort zone, you are in a state of asana. When we hold an asana steady and with ease, the affected muscles are in an isometric contraction.

Moving our body with control through Sun Salutations, entering and exiting an asana with control - at all these times we make use of various muscle contractions. And we also use concentric contractions, of course. For example, when we lift ourselves into a pose.

But, just as often, we will be in either an isometric contraction as we hold a pose or in an eccentric contraction as we control our bodies' movement against the force of gravity. An example of such eccentric contractions in Hatha Yoga are:

- Bending forward into Uttanasana (eccentric contraction of the hamstrings)

- Lowering our straight legs down from Shirshasana (eccentric contraction in the back muscles)

The take-away: Yoga for strength and flexibility

In Hatha Yoga, we move our body through warming-up and challenging back-bends. The eccentric contractions during these asanas and exercises strengthen and lengthen our muscles. In the steady postures such as the Shoulderstand, Plough Pose, Seated Forward Bend, the isometric contractions of the muscles promote strength and at the same time stretch the fascia. And as we hold the pose for a certain duration, we condition our muscle spindles, training them to tolerate more tension before applying the stretch-reflex and through applying.

Practice with these principles in mind and you will discover how intimately linked our nervous and muscular system are. As you tune into how a movement or posture feels and how it affects your breathing, you can train your muscular and nervous system to slowly adopt more effective and healthy patterns.

Resources:

Functional Anatomy of Yoga – David Keil

Get a free copy of our illustrated e-book 4 Surya Namaskara Variations for Vinyasa Yoga